Dictionary

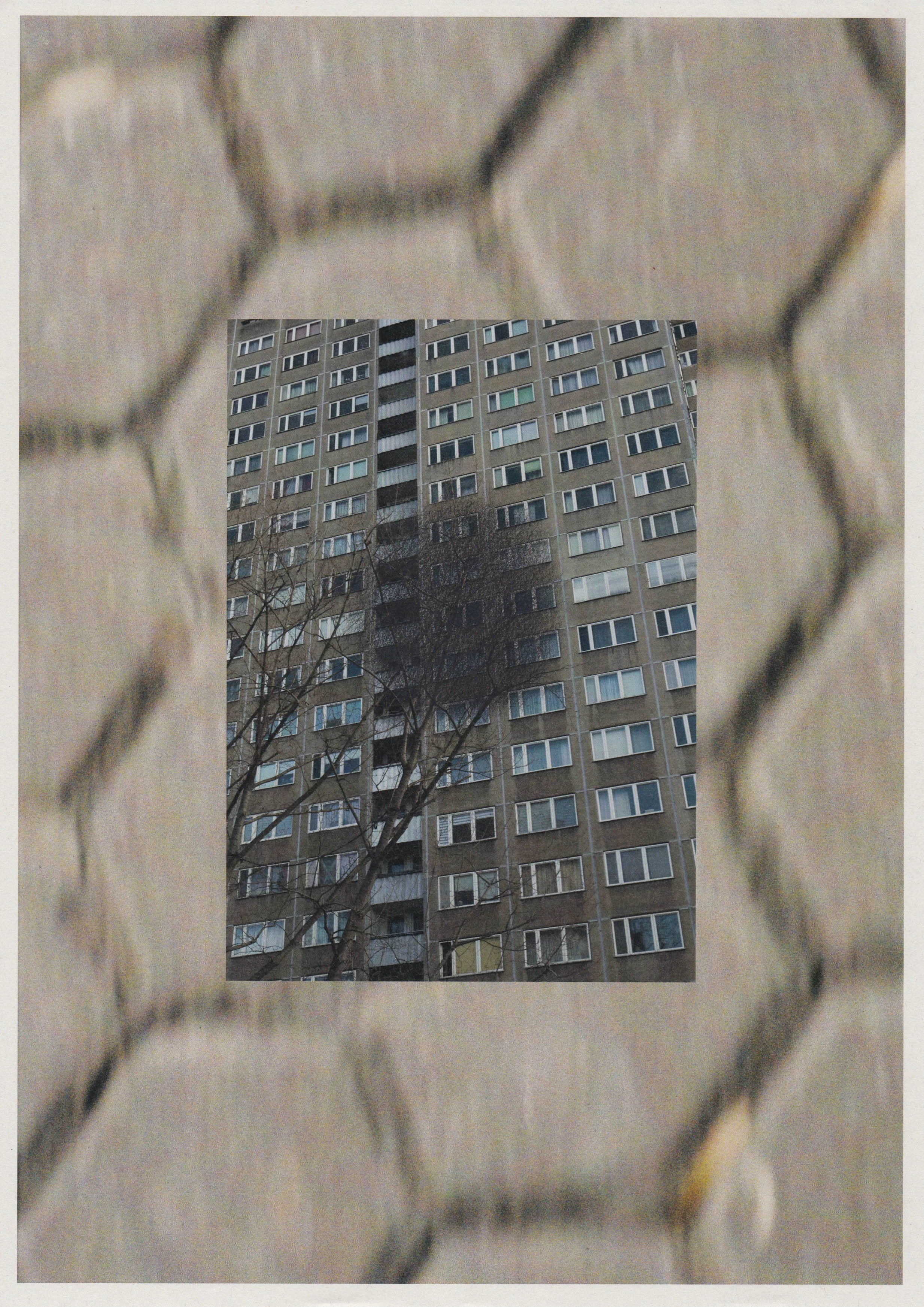

text, archive photography, colored pencils

A4My immigrant experience formed the basis of a diary-dictionary describing the most difficult periods of my integration process in my first year in Berlin. Living through the loss of my home and the search for myself in a new place, I observe my feelings and mental states, fixing them to share my story.

Dictionary

The project exists in the form of A4 paper sheets with short essays and an illustrative part.

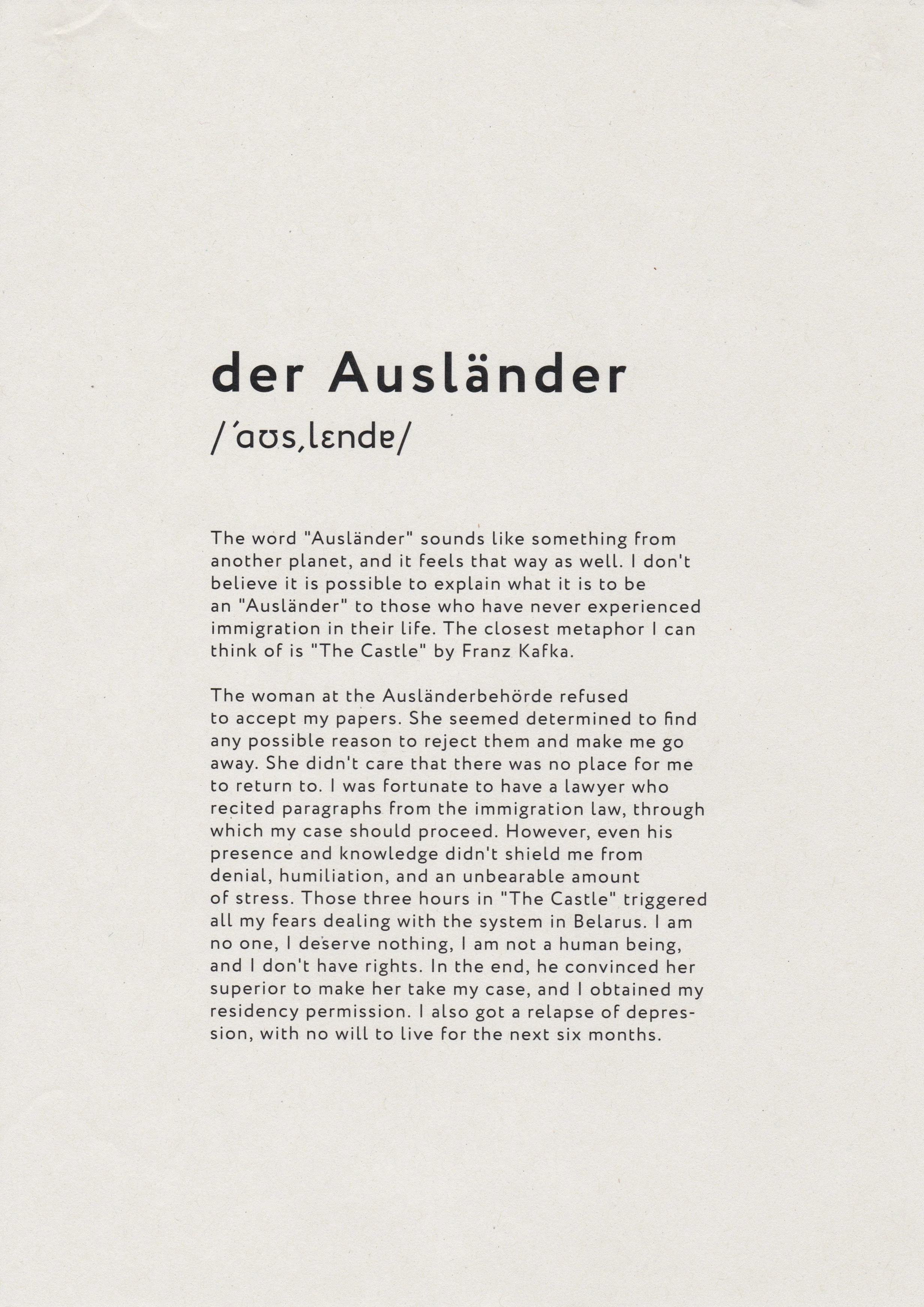

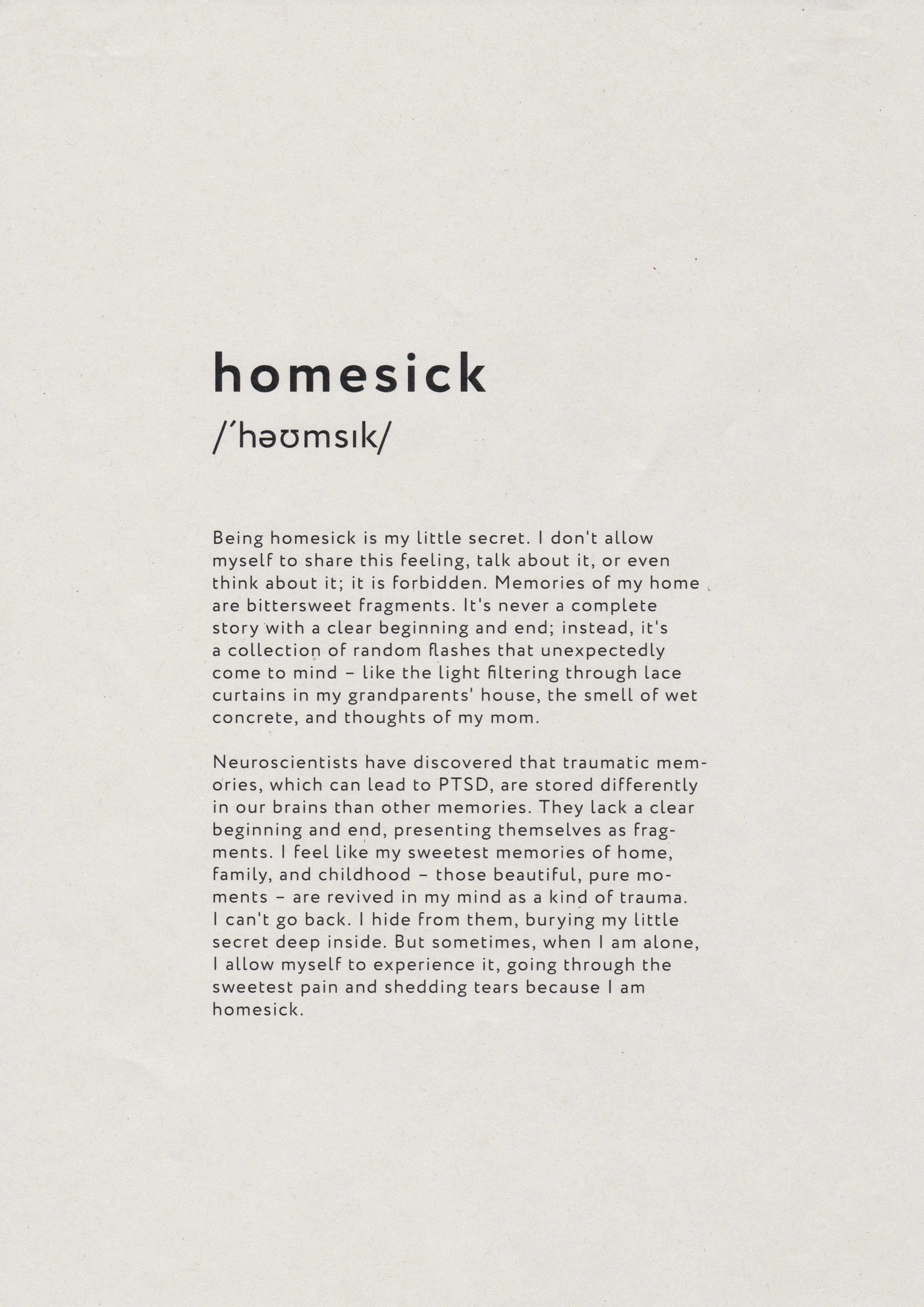

There are 4 topics: Homesick, Vulnerability, der Ausländer (“Immigrant” in German), Retraumatisation.

Berlin 2024